For this first edition of my blog I spoke with teacher, graphic designer and alternative process photography expert Cotton Miller, MFA, about his artistic development and how old-school printmaking processes can contribute to a contemporary vision for photography. I thank Cotton for his time and assistance in developing this article.

—Jon Wollenhaupt

JW: When did you begin taking pictures? What inspired you to take up photography?

Cotton Miller: It’s a complicated answer. My first introduction to photography was at a very young age. My dad is a graphic designer and has a lot of friends and colleagues who are professional photographers. Each year, one of those friends would take a portrait of my sister and me. To a kid, the setup was impressive with the lighting and everything. The prints we got back then were silver gelatin prints.

Cotton Miller: It’s a complicated answer. My first introduction to photography was at a very young age. My dad is a graphic designer and has a lot of friends and colleagues who are professional photographers. Each year, one of those friends would take a portrait of my sister and me. To a kid, the setup was impressive with the lighting and everything. The prints we got back then were silver gelatin prints.

My fascination with photography started then—but not from a process level, more from the shooting side. I was four or five years old at that time, so photographic processes were not at the forefront of my thoughts.

The first time I saw an image developed in the darkroom, the first time I saw an image magically appear on a blank piece of paper, was with a friend who was really into photography. He had set up a darkroom in the laundry room in his house and showed me the process of developing an image.

But I still wasn’t ready to jump into it yet, to really go after photography. I meandered around a bit, always doing different artistic media. When photography really took hold of me was at the end of high school, during my senior year.

At that time, I was fascinated by the movies of Stanley Kubrick. Because of his work, I started thinking about photography from a moviemaking perspective. I bought a box set of his movies on DVD, which included a documentary called Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures.While watching that documentary, I discovered that he was a still photographer first! That’s what got him into making movies. So, I’d say that realization about Kubrick is really the catalyst that got me on this road. I also realized that I needed to learn to create the image first, before I started to tell stories, which was different from the way I was always thinking about movies.

During my senior year of high school, I started shooting for fun on my own with a film camera that I borrowed from my sister. This is how I fell in love with photography, by shooting on my own, without any classes or instruction. By the end of my senior year, I thought, you know, maybe this is something I’d like to study in college.

The summer after high school, I spent a month in Alaska with the National Outdoor Leadership School. During that trip, I made a lot of pictures, which solidified something in me. I began to think this is something I could do for a living, that someone might hire me to go on a trip like this to take pictures. That inspiration made me want to seriously look into doing photography for a living and making it a career.

As soon as I came back from Alaska, I enrolled in the photo program at Houston Community College. There, I learned film-based darkroom processes. Then I moved to Austin and enrolled in Austin Community College to take the second level of photography. During my time there, I won an art competition with a photograph I made and printed on the last day of class, which made my professor, who was taking submissions for the show, laugh.

JW: Was the print still wet when you submitted it to him?

Cotton Miller: Almost. After winning the competition, I submitted that image to the Nikon College of Photography to be considered for the yearly Nikon book. I was given an honorable mention and my photo was included in the publication.

JW: Where did you get your undergraduate degree?

Cotton Miller: I first attended Austin Community College and then transferred to the photography program at Texas State University in San Marcos. That’s where I finished my photography undergraduate degree.

JW: Your dad is a graphic designer. How did his creative endeavors influence you growing up?

Cotton Miller: Yes, my dad is a graphic designer. He’s also a collector, as many artists are, and a furniture builder. Growing up, I was always surrounded by great paintings, prints, and artwork of various types, including furniture. He instilled in me and my sister a huge appreciation for art, which was a big influence on us. He gave us, starting at an early age, a visual syntax for art. His influence allowed me to start formulating what I appreciate in works of art and what I find interesting and engaging.

He always engaged us to help him with his work. Whether it was having us sand a piece of furniture or help to paint it, he always included us. I remember as a little kid going on press checks with him. He would put me up on the drafting table in the press room and have me find flaws in the print. He would point out a spot that wasn’t supposed to be there, and he’d say, “You see this? Find more of these and circle them.” All this experience was instrumental in training my eye from a young age.

My dad’s encouragement led me to the belief that I was going to do something creative. I didn’t necessarily know what it was going to be, but seeing my dad’s work and career as an example, I knew it was attainable.

JW: When did you first get introduced to alternative process photography? When did you start experimenting with those print processes?

Cotton Miller: I had a professor at Texas State University who was a painter and draftsperson. She also did some printmaking as well. I took an elective class she taught called Drawing Special Problems. Because I was a photography major, I wasn’t super excited about the class, and she could tell. She suggested that I use my photographs as a foundation for drawing. What really piqued my interest is when she told me about artists like Robert Rauschenberg, who did paintings that were essentially image transfers. I was fascinated by that idea, so I went to the store and bought a bunch of cheap paper and started doing tests and experiments to see how I could transfer images. I really loved that. It was my first discovery—that there are other things you can do that aren’t just straight printing of photography.

Cotton Miller: I had a professor at Texas State University who was a painter and draftsperson. She also did some printmaking as well. I took an elective class she taught called Drawing Special Problems. Because I was a photography major, I wasn’t super excited about the class, and she could tell. She suggested that I use my photographs as a foundation for drawing. What really piqued my interest is when she told me about artists like Robert Rauschenberg, who did paintings that were essentially image transfers. I was fascinated by that idea, so I went to the store and bought a bunch of cheap paper and started doing tests and experiments to see how I could transfer images. I really loved that. It was my first discovery—that there are other things you can do that aren’t just straight printing of photography.

At some point, I went to see a student show at the college, and I saw this photo created by a girl that I knew from the program. It was an architectural shot. Below the photo’s title, it said “gumoil print.” And I thought, what is that? Because the image didn’t look like anything I’d ever seen. It looked more like a painting. It had this quality that I just found irresistible. I went to my professor, who was the chair of the photography program, and I said, “What is a gumoil print and how do I learn to make one?” He said, “You need to sign up for my alternative process class, which is a class you need permission to take. I’ll sign your prerequisite form to get you in.” So, I signed up for the alternative process class that fall, and that’s when I first got into it.

The first demo he gave us was on cyanotypes, which is a typical starting point when learning alternative printing processes. After the demo I thought, I need a book! I’m so excited about this—I need to be able to read ahead. I asked my professor to recommend a book that I should get. He said, “Get The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes by Christopher James.” I immediately went out and bought a copy. From that point on, I was off and running and haven’t looked back since. And I just fell in love with alternative processes. Everything I do now has some kind of alternative process. This path led me to the opportunity to write a chapter for the third edition of Christopher’s book.

JW: In your current work, is there any one alternative printing process that you gravitate towards?

Cotton Miller: Currently, I’m in this kind of weird place creatively because I’ve been doing so much work printing other people’s stuff that I just put my own work aside. But now that I’ve returned to Santa Fe to work and teach, I’m feeling invigorated again. I’m making things that I find interesting or clever or engaging. And I’m not really worried about the audience as much right now or what the work is saying. I’ll just get an idea and make it.

Cotton Miller: Currently, I’m in this kind of weird place creatively because I’ve been doing so much work printing other people’s stuff that I just put my own work aside. But now that I’ve returned to Santa Fe to work and teach, I’m feeling invigorated again. I’m making things that I find interesting or clever or engaging. And I’m not really worried about the audience as much right now or what the work is saying. I’ll just get an idea and make it.

I started making cyanotypes recently, which is a process that can be tough for some photographers to deal with conceptually because of limitation of making images that are rendered predominately in blue —a color that has a unique psychological impact.

I like the cyanotype process for where I’m at right now because it allows for easier execution, which enables me to concentrate on my ideas. I like that aspect of the process because I’m pulling back a bit from where I was in graduate school where we were always pushed towards more and more complexity. Right now, I am enjoying trying to say more with less. And I’m making work for myself instead of other people, which is what I feel like I’ve been doing to a certain degree since graduate school. It is nice that I’ve been getting lot of great response to my cyanotype prints from the people I share them with.

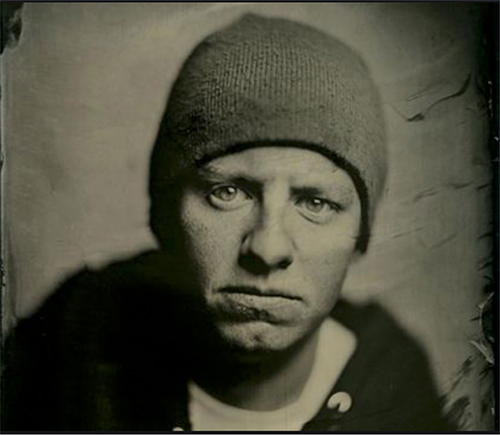

All that said, my favorite process is still shooting wet plate—making tintypes, shooting Ambrotypes, working in an old process that predates film. It’s such a unique thing. I just love it. Most people are familiar with it as an antiquated process. They’ve seen old images made this way, but they’re still not used to seeing wet-plate images made to express something contemporary.

What I really like about the process is it has an element of performance art in the way it’s created. I like to get the person I’m photographing really engaged with the process. The finished image is one-of-a-kind original, which I think is becoming more desirable these days because it is not a product of mass production. There is some serendipity involved in making an image this way, and some flaws that can be kind of cool.

JW: Is the alternative process photography movement a reaction to postmodernism’s mass production aesthetic?

Cotton Miller: Yes. There’s pushback but without the elitism of old-school modernism. Most of us who are working with alternative print processes, ones that were developed long ago, do so not out of merely mimicking past styles but with the intention of pushing the art of photography forward into new realms. We experiment with techniques such as cyanotype, carbon transfer, gumoil, and wet-plate printing not for novelty’s sake but to find a new visual language and personal expression. We embrace the craft of past processes to learn where we can take them.

Also, we make these types of prints because of the inherent flaws that are inevitable in the process. And we embrace those flaws. We are opposed, in a sense, to perfection, which is the ultimate goal of mass production—perfection and predictability. Those imperfections can be a type of signature, a stamp of originality.

There’s a certain irony in that most people I know who practice the craft of these printing processes share what they know. They teach and write books. The community of alternative printmakers always feels inclusive to me, the opposite of elitism. Yet at the same time, these processes are difficult to master and may not be for everyone. They take commitment and discipline to get desirable results, to attain interesting, compelling imagery. So, the community is small, but growing.

JW: Is there an increasing resistance to digital photography ?

Cotton Miller: Digital photography has become so technological. The camera can find the face, set the focus, make the exposure, and so many other things. And because with digital we can shoot lots and lots of pictures cheaply, quickly, make more frames, store more and more photos on a card, it all seems to contribute to less careful and less thoughtful approach to taking pictures.

Cotton Miller: Digital photography has become so technological. The camera can find the face, set the focus, make the exposure, and so many other things. And because with digital we can shoot lots and lots of pictures cheaply, quickly, make more frames, store more and more photos on a card, it all seems to contribute to less careful and less thoughtful approach to taking pictures.

I’m not saying one is better than the other, particularly now that we can actually say digital is good. You know? We couldn’t say that 10 years ago. But now we can pretty much go, yeah, digital’s here and it’s a valid way to make imagery. But I still see a perceivable quality difference between a chemical print and a digital print. I think what alternative process printmakers are looking for is something more organic that celebrates the random incident, the chance that happens when taking photos and making prints.

The converse of digital photography is shooting wet plate, because it takes so much attention to make one. You have to be very considerate of every little thing that you’re doing. You have to examine things carefully before making a picture. Shooting wet plate has trained me to be a better photographer; it has helped me tighten my vision, and, as importantly, it has made me slow down, and that helps me find the moment in which all considerations have merged into intent and I’m ready to capture an image. What I’m looking for, what I’m trying to discover, to capture, and to reveal to the viewer of my work is what Roland Barthes called the punctum—that indescribable, inexplicable thing that pierces you when you see a great image.

JW: How can alternative process photography, which utilizes many printing techniques developed more than 100 years ago, contribute to a modern vision of photography?

Cotton Miller: That’s a really good question. And that is what I think a lot of artists struggle with. When I mentioned Christopher James earlier, it was because I was in his MFA class at Lesley University in Boston, which was the first Alternative Process MFA program in the world. Christopher wrote the The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes. When I first met him, he told me he was starting an MFA program at Lesley and wanted me to apply.

I applied and got into the first class, which was composed of students handpicked by Christopher. For our first jury, Christopher brought in a panel of 14 amazing active artists, writers, and curators to critique our work. We were all working in various alternative processes, and we were challenged on what we were doing. The jurors really pushed us on why we were doing these processes. They asked: Are you doing it just because it’s pretty, novel? We had to give a solid reason on why we choose a particular process.

The jurors were not looking for a specific answer, but their intent was to get us to think. Just because I made a print using platinum palladium process doesn’t necessarily make it a great image. The process itself can’t transform a mediocre image into a great image. They were trying to push us to find ways to use those processes to create a new language.

Because these jurors were so renowned and influential, you start to realize that you’ve been making work to please them, to address ideas they brought into the conversation about your work. And if you’re not careful, you could begin to lose a little something of your own vision in the process.

Right now, I’m making work for myself. I am trying to extract myself from the graduate school mentality of making work for other people. I’ve been reading a lot about other artists and what they say about finding your voice as an artist. They all say make work for yourself. Don’t work for other people.

I feel strongly that once I take the time to focus on myself and dial into my own voice, people will start coming around to see what I’m doing. And they will recognize something authentic in my work. And hopefully, buy some prints!

And I’m getting there. I have had a lot of amazing feedback from some of the new prints I’ve made because I’m trying to do things that aren’t presented in a traditional frame. I got tired of seeing the same rectangle or same square over and over again, so I wanted to make work that didn’t have a traditional border, where some of the image actually bleeds out into the border. I’m doing some things that are more modern and don’t look like classic cyanotypes.

I’m also exploring ways to blend my graphic design sensibilities into my work. I’m using these old processes to inform and guide the way I work now. I’m using them to create something new, using them to create a more modern syntax rather than merely mimicking something old.

JW: Is there a particular image you remember making in graduate school for which you received serious pushback from some of the jurors? What did you say to defend it?

Cotton Miller: I created some MRI etchings for which I received the most interesting feedback. In fact, I was challenged as to whether or not they were even photographs! Some jurors seemed to think that an MRI itself was not a photograph. Luckily, there were a couple of physicians on the panel who asserted that an MRI machine is definitely a camera—a very fancy, very expensive camera that uses magnetic waves to create the imagery. So, how is it not a camera?

Cotton Miller: I created some MRI etchings for which I received the most interesting feedback. In fact, I was challenged as to whether or not they were even photographs! Some jurors seemed to think that an MRI itself was not a photograph. Luckily, there were a couple of physicians on the panel who asserted that an MRI machine is definitely a camera—a very fancy, very expensive camera that uses magnetic waves to create the imagery. So, how is it not a camera?

My process in working with the MRI images involved etching them into copper and then putting patinas on the copper. Still, a few jurors did not consider final result a photograph.

Following their reasoning, one could make the argument that a digital image, a digital print, isn’t a photograph either because we’re talking about the process of writing with light. And a digital camera doesn’t write with light in the same way that film does. Right?

My defense was that this same argument comes up anytime a new medium is created, and we have to ask, “Is it a photograph or is it something else?”

Additionally, I said I could ink and press those copper plates into paper, which I did, and I showed them the prints I made that way. The process I used for the MRI images harkens back to photogravure, which is an intaglio printmaking process in which a copper plate is grainedand then coated with a light-sensitive gelatin tissue—a process that goes far, far back into the earliest days of photography. So, my MRI images represented something that reached into the historical discourse of photography.

And in a modern sense, how are MRI images any different than digitally produced photography? I eventually got my point across and they agreed.

It was exciting, too, because the physicians on the panel loved the work. They said they liked the fact that I had taken imagery that was very familiar to them and had created a completely new expression and articulation for that imagery.

JW: What was the concept for that body of work?

Cotton Miller: The body of work was on the topic of MS, and disease in general. Before I started my MFA program in Boston I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. These images were made while tracking my daily treatments. The patina technique was a way to express the idea that there are things that can corrode but, at the same time, can protect. This relates to my thesis, which was about artists throughout history whose work and perspective were intertwined with challenges they faced due to a physical ailment, medical condition, or emotional trauma they experienced. The idea was that the physical or emotional challenges those artists faced, the pain they endured, were an integral part of their creative force and process, and why they became the renowned artists we celebrate today.

Consider the case of Mary Shelley. There is the theory that her motivation to write Frankensteinwas related to the tragic deaths of her children at very early ages. The creation of Frankenstein was born in the darkness of her loss; her grief drove her to want to bring something back to life.

“The work is about perception, and how one deals with trauma, with a life-changing event. I like the idea of the mind and the brain. The brain is physical, and the mind is subjective.” – Cotton Miller, from a Boston Globe article by

JW: Let’s talk more about the process you used to create the MRI images. Can you walk us through the process?

Cotton Miller: I had several MRIs of my own and used some freeware to rip the them from the files the doctor created. I

Cotton Miller: I had several MRIs of my own and used some freeware to rip the them from the files the doctor created. I

wanted to create a series, a sequence, about the passage of time.

I used Lazertran, which is a waterslide decal material that allows you to transfer photographic images to various kinds of surfaces. In this case, I transferred the MRI images to copper plates. I would change my approach depending on the outcome that I was looking for—sometimes I would use a negative, and other times a positive. After I applied the decal to the sheet of copper, I would bake it on in the oven and then remove the decal material with alcohol.

I would then go up to the printmaking studio and put the plate in a ferric chloride etching bath and let it etch through the copper. And then sometimes I would ink up the image before I put it in the etching bath. I applied an aquatint layer so that it would hold ink once I etched it. I would then apply different patinas to the copper.

The reason why I was using copper plates was because of the MS theme in my work—because MS is a breakdown of communication between your synapses in the brain. I wanted to speak to the language of electricity, which is why I used copper, which worked perfectly as a conceptual tie-in to the MRIs and to the breakdown of the brain’s circuitry. Conceptually, I also found it fascinating that the patinas act as a corrosive and also provide protection.

JW: Was this a completely unique process you created for those images?

Cotton Miller: Yes. As far as I know, I’m not aware of anybody doing patinaed metal with prints. I got the idea to work with this process during my undergraduate program. In fact, the first copper patinaed piece I made in my undergrad program, I ended up showing to Christopher James here in Santa Fe. Upon seeing it, he said, “I want this piece to be in the next edition of my book.”

JW: In the field of alternative process photography, which artists would you like to give a shout-out to for their contributions?

Cotton Miller: Obviously, Christopher James had a big impact on me. Also, Dan Burkholder is someone who I have learned a lot from and has become a close friend. He came up with the process for printing digital negatives that is used in the alternative process photography darkroom. He also wrote the first book on the topic. He’s very forward-thinking and is an early adopter of new technologies. He’s always thinking about how to merge the new with the old. That’s why we’ve always gotten along tremendously.

Jill Enfield is someone who has made major contribution to the world of alternative processes photography. She’s multifaceted and very talented. She prints using a lot of different processes and teaches workshops as well. I really love her work and her contribution.

Christina Z. Anderson is a major force in the field. She’s written excellent books on cyanotype and gum bichromate. I’ve always admired her work and how she streamlines and creates workflows. I’ve known several of her students. They just love her to death. I hope I get to meet her one day.

Cotton Miller’s Bio

Cotton Miller is a photographer, graphic designer, craftsman, and educator. Cotton is a graduate of the 2013 inaugural class of the MFA Photography and New Media program at Lesley University College of Art and Design, created by program director Christopher James. His work runs the entire spectrum, from one of the first photographic processes to digital multimedia. Cotton was featured as one of “Six Art School Grads to Watch” in 2013 in The Boston Globe.

Before getting his MFA in Boston, Cotton was the digital lab manager at the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops in Santa Fe, New Mexico Because of his wide range of knowledge, Cotton brings simplicity to digital technology while connecting to artistic tradition both through explanation and execution. Cotton has worked with some of the world’s best in the fields of photography, art, and education, and seeks to inspire current and future generations about photographic and artistic traditions.

See more of Cotton Miller’s work at http://www.cottonmiller.com

Honors, Awards, and Exhibitions

- Look 15: The International Photography Festival:Liverpool, England, May 15–31, 2015, curated by Emma Smith.

- Texas Photographic Society—Alternative Processes Competition: April 6–May 8, 2015, Options Gallery, Odessa College Odessa, Texas.

- “Six to See: A Showcase of Top Grads from Boston’s Art Schools” by Cate McQuaid, The Boston Globe , April 19, 2013.

- MFA Thesis Exhibition: AIB Gallery, 700 Beacon St., Boston, Massachusetts, April 24–May 1, 2013.

- Faculty Group Show: AIB Gallery at University Hall, October 2012,

- Panopticon Gallery; AIB MFA Gallery Group show, February 2012.

- MFA in Photography Inaugural Exhibition:Group Show, AIB Gallery at University Hall, Boston, Massachusetts, February 22–March 10, 2012.

- Salon at Photo-Eye Bookstore: Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2010.

- Texas Independent Press Association: Award for Excellence, Newspaper Division 2, 1st Place, Sports Action Photo, 2007.

- Society of Professional Journalists: Region 8 Mark of Excellence Award 1st Place, Sports Photography, 2006, 2007.

- 28th Annual College Photography Contest: Photographer’s Forum Magazine, co-sponsored by Nikon, finalist.

- Week in the Life Photo Award Recipient:Texas State University San Marcos Student Exhibitions, 2006–2007.

###

About the Author

Jon Wollenhaupt is a Sacramento, California-based artist who works in digital and alternative process photography. His work has been shown in galleries in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and Portland.

Contact: Jon can be contacted via email at jon@jonwollenhauptphotography.com

Comments are closed.